| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

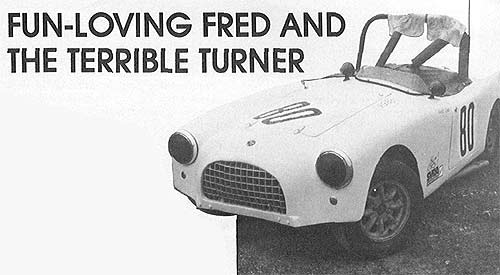

The Turner was no beauty, and sometimes was used to hang laundry to dry. |

| Give an Englishman a piece of metal and he'll do something silly with it. That's what my good friend John Welch used to say. And he should know, because John raced English cars for years (including the most outrageous XKE you ever saw, but that's another story). At any rate, there is no doubt that Britain is the oddball car capital of the known world, and so it is perfectly natural that a car like Fred Leib's Turner comes from The Foggy Isle.

Fred started racing way back in the mid-fifties, when the sport was in its infancy here in the U.S.A. He had a bathtub Porsche that he couldn't really afford, and ultimately sold it to buy a Turner. Now, tell the truth: most of you haven't the faintest idea what a Turner is, do you ? Jack Turner was an English club racer and self-styled automotive entrepreneur who, in 1954, embarked on a venture building small displacement sportscars with strong racing pretensions. The first Turner model was the 803, of which around 30 were made, followed by the infinitely more popular 950S (a whopping 150 built!), and then came the handsomer and more powerful Turner Mks 1 through 3. All Turners shared a similar chassis layout, with a ladder-type frame welded up from 3-inch tubing, stressed sheet undertray, and topped with a somewhat odd (to be more than charitable) fibreglass body. The front end of Fred's 950S looks like a caricature of a Ferrari Barchetta, complete with cast alloy eggcrate grille, while the rear view is right up there with the Daimler SP250 and Tatra Sports for outright weirdness. I don't quite understand the aesthetics of the two dinky, vestigial fins and the sagging paunch of a decklid, but I suppose that beauty's in the eye of the beholder and all that rot. Besides, the Turner's nifty underpinnings more than make up for any lack of grace in the cosmetics department. Independent front suspension, featuring Austin A35 bits and a unique rear axle layout yield impressive roadholding, as we shall soon see. Powerplant of the 950S is the evergreen BMC "A" engine, as found in countless Sprites, Minis, Formula Junior, etc. Fred's particular motor displaces 998cc, and while state-of-the-art technically, is wisely kept below a fragmentation-bomb state of tune. After picking up the Turner in late 1958, Fred got the wild idea that he should run it in the 1959 12 hours of Sebring with Smokey Drolet (one of the first and best female American sportscar racers) slated as co-driver. Smokey had been driving TR2s and TR3s for the Southeast Triumph distributor, and doing very well at it. So Fred wrote Jack Turner and managed to wheedle an entry fee out of the factory, but didn't even bother to bring the 950S down to Florida because they were listed as an alternate and not given much of a chance to make the field. "Heck," Fred recalls, "we had our credentials, so we figured we'd just go down and watch. Imagine our surprise when we found out we were first reserve and a shoo-in to make the race! We had to call some friends back in Huntsville, scramble around and find a trailer, get into my garage, load up the Turner and a few tools, and get it all down to Sebring in a big hurry! Fortunately, Smokey's boyfriend's aunt or something owned a shop near Sebring where they worked on orange grove sprayers and stuff like that, and that's where we prepped the car for the 12-hour. It had never been in a race before that! Had it ready for Wednesday practice, too. As endurance races often will, Sebring turned into something of an ordeal for the quasi-official Turner FActory Racing Team. "It rained a lot that year, which actually helped us. The Turner sat up pretty high compared to the all-out sports-racers, and we could motor through the deep stuff while they would be skating along on their bellypans. I think we were among the five or six quickest cars when the rain was really bad. Then the front trans seal went and started oiling up the clutch. It got to where every time we'd bring it in for a fuel stop, we'd jack her up and unload a carbon tet fire extinguisher into the bellhousing to clean the oil off the clutch. But we finished! Took a third in class, too. Then we loaded up and towed home on Sunday, and I drove the Turner to work on Monday morning!"

Fred raced the car some more in the Southeast, but then had to follow his job to Europe for a few years. When he returned, Fred had some trouble relocating his 950S, and ultimately had to buy his own car back from the gentleman who had it in storage. At the time, the SCCA didn't recognize the Turner as production car, so Fred ran it against pure sports/racers before switching to a more normal (or is it normale ?) Alfa Guilietta. Besides racing, job, and putting six kids through school (ulp!), Fred took on the responsibilities of race chairman for the local SCCA region and wound up doing a lot of the trackside P.A. announcing when not otherwise occupied. It was in that capacity, in 1980, that he made his first SVRA vintage event. "Aw, it was great. These were my kind of cars. That's when we decided to bring the old Turner out of mothballs. I could do it then, because I was free." Fred defines "freedom" as "no more kids suckin' on the checkbook, and the dog dies." He flopped the Turner over on its back, replaced all the rusted, worn-out pieces, and Fred and the little blue car have been regulars around the SVRA ever since. I had a chance to test drive Fred's car at the SVRA's Bahama Speed Week (which is kind of an eight-day party with a little racing thrown in ... see full story next issue), but the conditions during my session were less than ideal. To begin with, the Freeport Street circuit is real narrow and a tad unforgiving in places, with the odd curb, tire wall, and concrete barriers ready to lay waste to poorly directed momentum. On the plus side, the circuit is a ball to drive, with some great rhythms to it. This particular morning, however, it was drying out after a hard rain, and there were large damp patches to contend with. Beyond that, I was a wee bit foggy-headed from several nights of typical Bahamian Vintage Racing Behavior. Mine was hardly a unique condition during Grand Prix week in Freeport/Lucaya!  Fred and share largish derrieres (in fact, we would be better off sharing just one!), so I found the seat nice and comfortable and the driving position excellent. You'd think a comfortable seating position would be expected in a racing car, but you wouldn't believe how many of the damned things pinch this or cramp that or leave your arms cranked up at goofy angles. A comfy driver should be a first priority, period. The Turner's shifter falls, as they say, readily to hand and is connected to a very sophisticated gearbox with Webster internals. That's to say, it's a full-out, non-synchro, close-ration transmission like you would find in a Formula Car or a Sport-Racer stuffed into an ordinary Austin casing. First gear is tall enough to be just the ticket for slower turns, but this unfortunately makes the little bugger a tough nut to get rolling from a dead stop, and I'm afraid I left the acrid aroma of clutch lining hanging in the air every time I tried to get underway. Sorry Fred. I had trouble getting used to the pedal arrangement, as they're skewed way over to the left and Fred has a large, L-shaped heel-and-toe plate fitted to the gas pedal. I kept catching a bit of it every time I went hard on the brakes the first couple of laps. Disconcerting, to say the least, when you try to slow down and find yourself on the throttle and accelerating instead! Especially on a damp track lined with big concrete blocks! I'd never really driven anything quite like the Turner (a Sprite, for example) and found the small size, narrow track, and short wheelbase a little tricky. You like to lay a racecar over into a slip angle and have it set up into a nice, stable, elegant drift through the radius of a corner. Maybe the Turner will do that, but on first blush, I had the feeling it would sooner twitch and skitter like a go-kart than scythe through in one fluid, continuous arc. So I took it easy, like Guest Journalist drivers always say they will - but seldom do! As the laps reeled by, I began to pick up the feel and flavor of the turner. There isn't an awful lot of power (hey, what do you want from 998cc ?), and what there is lives mostly between five thou and 7500. But the car is very light and quick, so it motors around to some very respectable lap times, even if it can't really mast you into the rollbar padding with fierce acceleration. The brakes are very, very good, slowing the car without drama or fade, and may be on of the car's best assets. All in all, it's a handy little package that can be flipped and flicked about in the tight stuff like some kind of motorized whiffleball. Even better, Fred's car has that 'complete' feel you only find in a well-campaigned racecar. Shiny restorations and mirror-perfect paint just don't get the job done when it comes to all the umpteen-thousand minute details that make up a decent racing machine. So I enjoyed the car a lot. But I enjoyed evenmore Fred's war stories and most especially his attitude towards Vintage Racing. He drives hard and the drives well, but Fred never loses sight of just what Vintage is all about. Like f'rinstance at the concours, where Fred knew his Turner had no chance against the ridiculously immaculate spit-and-polish opposition. So he resorted to outright bribery! When the judges (including Yours Truly) arrived on the scene, Fred opened the Turner's oddly-shaped trunk and produced racing-motif party hats, blowout noisemakers, long-stemmed glasses, and the cheapest bottle of ice cold champagne you ever saw in order to brighten out day (and perhaps cloud our already-suspect powers of reason?). Or howabout when Fred got accidentally blackflagged while running first in class and second overall during Saturday's qualifying race. He dutifully called into the pits, losing his hard-fought position, only to find out the nasty black was for somebody else, and he had been called in by mistake. Sure he was disappointed. Angry, even. You would be, too. But after a while he shrugged it off and came back to enjoy the rest of the program and run on hell of a race on Sunday. This besides handling much of the burden in the announcer's booth. Stuff like that: hard driving, sportsmanship, and a willingness to shoulder some of the responsibilities of running an event instead of just sopping up all the fun are what sets Fred apart. Which is why the SVRA recognized him at Sunday night's year-end banquet with the highest honor they have to bestow: SVRA Driver of the Year. It was something to see, all right. Fred got all chocked up, the crowd went nuts, and for once he found himself in front of a microphone with nothing much to say. Except "thanks".

Yeah, it was a pleasure driving Fred Lieb's Turner. But it was a damn privilege getting to know him. |