| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

| Turner Sports Cars | Articles |

|

The Turner factory, located at Pendeford Airport, Wolverhampton, is relatively new and in fact little had been heard of it over here until 1958, when this marque won the team Challenge Trophy in the British Autosport Series Production Sports Car Championship and took first and second in the 1100 cc class. Then it was that the knowing American sports car enthusiast of modest budget began to ask a lot of questions; especially when successes in this country included a 1957 calss win in the Florida Six-Hour Sam Collier Memorial Trophy race, and a second last year.  So persistent were thest queries that after a couple of good looks, Dale Smith, owner and founder of Tri-City Sports Cars in Massillon (near Akron) Ohio, entered into a factory agreement which appointed him Turner distributor for the entire United States, with the sole exception of Flordia. When Mr. Smith, who is a mid-western sports car driver of some renown, telephoned to offer us an exclusive road test of the 1959 Turner, we were both interested and flattered. The test, which is the subject of this article, involved a flight from New York to Akron; but as things turned out, the trip was more than worthwhile because I had ample opportunity to try out not just one but two versions of the Turner. The bonus ride, in additionto the Turner SPR-60, was a new and intriguing Coventry Climax version using only the Stage I tune, yet an interesting portent of things to come. Before we get behind the wheel or start the watch, let's take a close look at the basic structure of the Turner, which serves all its models. The frame is a rigid T-shaped tubular job with large main side-members made up of parallet 3-inch diameter tubes, using 16-gauge steel. The rear half of this frame features parallel drilled outrigger members designed to equalize and distribute the stress of the fibergalss body. The front suspension uses BMC Austin A35 components, with fabricated brackets and wishbones of pressed steel. Forged upper suspension links are directly connected to Armstrong hydraulic damper spindles. Steering is of BMC rack and pinion design, while the solid rear axle also originated as an A35 component. The Turner's rear suspension, however, is entirely different from that of the Austin. Here, training links are used in conjunction iwth short transverse torsionsprings, the kicked-up frame side members providing vertical anchorage for a pair of telescopic shocks which have their lower eyes connected to the axle. Rubber bushings are used at all the relevant points of the rear suspension, and in addition a short Panhard rod connects the axle casing with the left side of the frame.  This year, the front brake drums of the Turner have been increased in diameter from 7 to 8 inches and in width from 1¼ to 1½ inches, while a two leading-shoe lay-out is featured. The rear brakes remain unchanged with 7 x 1¼ drums, and it must be said that on the Dunlop wire-wheeled version of the Turner, even the new drums look alarmingly small. I, for one, would not care to run around Sebring for 12 hours with these binders. Yet in practice they have proved intirely equal to repeated hard stops with no noticeble fade or distress.

This year, the front brake drums of the Turner have been increased in diameter from 7 to 8 inches and in width from 1¼ to 1½ inches, while a two leading-shoe lay-out is featured. The rear brakes remain unchanged with 7 x 1¼ drums, and it must be said that on the Dunlop wire-wheeled version of the Turner, even the new drums look alarmingly small. I, for one, would not care to run around Sebring for 12 hours with these binders. Yet in practice they have proved intirely equal to repeated hard stops with no noticeble fade or distress.

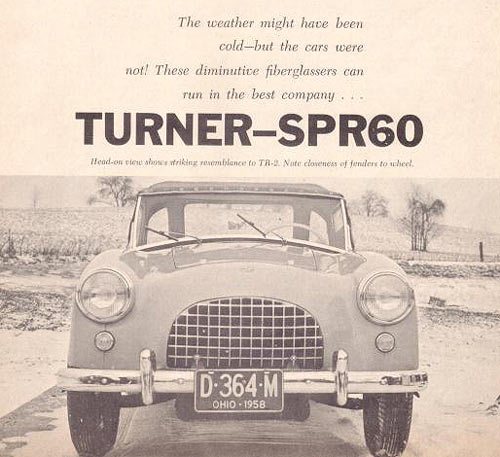

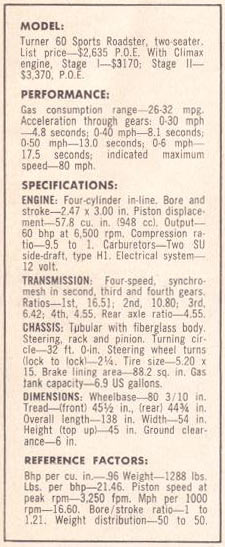

Naturally, one of the interesting things about the Turner is that it offers direct competition to the Austin-Healey Sprite, whether as a sports-racing car or a drive-to-market orm of economical transportation. For instance, both makes use the BMC A-type A35 pushrod engine and the A35 four-speed gearbox, but designer Turner has fitted a set of gears of slightly lower overall ratio that retain approximately the same relationship to each as the regular transmission but suit the car especially well. As another example, the Sprite's rear axle ratio is 4.22 while that of the Turner is 4.55. As to models, there two versions of the BMC-powered Turner - Model 950 with the stock engine putting out 43 bhp at 5,000 rpm and the hopped up SPR60 which was one of the test cars handed over to me on arrivial. This model uses a slightly more radical cam, a lightened flywheel, an exhaust header designed to improve flow and a beefed-up pressure plate and clutch face. Supposedly, too, the unit has been balanced. Compression ratio is upped from 8.3 to 9.5. Heavy duty Vandervell cadmium-bronze bearing inserts are featured. Now let's get the two test cars clearly identified. The SPR60 was light blue with silver knock-off wire wheels, dark blue leather upholstery piped in white, a black carpet and a pale top of leatherette material. The Conentry Climax version had red bodywork, black upholstery with white piping, black carpets and silver disc wheels on bolt-on type. Besides the Stage I Climax engine (75 bhp at 6,000 rpm) and some unspecified gear rations, this machine also carried an optional feature available at no extra cost when specified by the customer. In place of the rear laminated torsion bars, coil springs were substituted which enclosed the telescopic shocks.  Since the bodywork and details on both cars were identical, the following measurements are interchangeable: - interior width is 43 inches door to door with and adequate 8 inches of elbow room between seats, provided by the driveshaft tunnel. The Turner is easy to get into or out of because of its no-nonsense, vertical doors, 23 inches wide. These, incidentally, are opened by means of an unusual outside pushbutton type of latch. You sit comfortably in a well upholstered, form-fitting bucket seat 16 inches deep and 15½wide, with a seat back 21 inches high affording ample support where it is needed most. Seat adjustment is a bit crude; it consists of a pair of nuts and bolts which go through holes in the seat base and the floor. Four holes at one-inch intervals provide the range of adjustment, but with the seat fully back (as it was on both test cars), maximum distance from pedals to seat edge is 25 inches, not an awful lot for a tall man. However, there is still an inch between the seat back and the rear body bulkhead, so that presumably additional holes could be drilled to take advantage of this extra space. The Turner features a multiple spring-spoke type of steering wheel with a plastic-covered rim and a telescopic adjustment. Personally, this feature I can take or leave, and the same goes - I think - for any driver of above average height because the 16½-inch wheel must be pushed all the way down to allow enough armroom. I think the car would benefit both in looks and comfort by having a slightly smaller steering wheel. About one inch off the diameter would be fine. The fiberglass bodywork is this interesting little sports job is surprisingly well finished. It is well anchored to the chassis by means of a welded sheet steel body sub-frame which takes the primary stress and promises freedom from rattles. The cast-aluminum Turner grille is neat and simple, and from certain angles - three-quarter front, for instance - the car looks exceptionally pretty with the top down because it displays a hint of compound curves and appears to gain in length and therefore in proportion. Viewed in profile, however, the car is rather slab-sided and would gain much if the entire silhouette were lowered three or four inches.

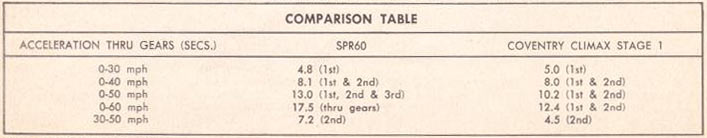

The top fits over a collapsible tubular framework andis secured by press-type fasteners to the top edge of the windshield and push-pull fasteners to the cockpit contour. Sidescreens fit quite snugly. Rear view with the top up is excellent because of a plastic area affording 213 sq. in. of vision, plus a pair of wedge-shaped side windows. Too, the heater - standard equipment for a change - does a real bang-up job. I make a special point of mentioning the heater because on arrival at Akron I found the snow thick upon the ground and was greeted by blasts of icy air just a few degrees above zero. Furthermore, some light snow flurries at intervals heralded distinctly unfavorable conditions for testing sports cars. Luckily the local road surface was not yet slick enough to affect traction to any extent. Out we went, then, taking the red Coventry Climax machine first - and delightful it was to handle. The steering is so positive and direct that for the first couple of miles its affect is disconcerting; but you soon get used to it and begin to enjoy this lively machine. Clutch action is smooth and positive. The short, rigid gear lever falls just under your hand and the gearbox is a real pleasure to use although a trifle noisy in the indirect gears - and I don't mean just the non-synchromesh low. There is also, of course, an appreciable amount of engine noise, but what enthusiast doesn't get a charge out of listening to a sweet-running Climax as it builds up the revs toward a provocative crescendo that seems to say: "Okay! I can so still higher if you like. Nothing to worry about!" The acceleration comparison chart tells its own story. With the Climax-powered machine - which has relatively poor low-speed torque - you gain nothing over the BMC engine at the start of the drive; but from 50 mph on up you simply run away. With the Climax, I never once had to get out of second gear to reach the required speeds, yet the tach never rose above 5,500 rpm and was mostly around 5,000. What this little bomb would do with the Stage II or Stage II Climax engines isn't hard to imagine. Sixty wold undoubtedly come up in well under 10 seconds. As it was, the engine of the test car was not even tuned. The machine had landed with a blown gasket and this had only been changed the night before. Another thing was that the engine never got anywhere near operating temperature. We forgot to blank off the radiator, and due to the extreme cold the temperature gauge barely got off the peg at around 35 degrees centigrade. To return for a moment to the department of gripes, the pedals on both cars seem too close together while the clutch pedal is so snug to the body side that you have virtually nowhere to park your left foot. This I think is a serious fault, though not hard to remedy. Another thing is that with the top up an adult of anything above average height has zero clearance between his head and the interior lining. Wearing any kind of a hat is out of the question, therefore, and the only way to correct his problem would be to lower the floor-line, as the seats themselves are not built up. On the other hand, the rear trunk reveals a gratifying amount of space for so compact a car - about 9 cubic feet, in fact, although the spare encroaches on some of this room. Still, you can pack a good-sized twosome suitcase in there plus sundry packages and close the lid without trouble. The door pockets, too, are of useful size for stowing odds and ends. The glove box, on the other hand, is a token affair. Getting back to performance and handling, the Climax machine has the engine set well back so that weight distribution remains unaffected and the car retains its marked understeer. When taking a sharp turn on slick surfaces I broke the rear end loose just enough to test control and found response immediate and reassuring in the manner of a throughbred sports car. Because of the miserable conditons, high-speed cornering and maximum speed tests were not made, but I played around enough to gather the definite impression that the Turner would be loads of fun to dice with in a race. It really is a delightful little car to handle, and that feeling grows on you with every mile. The SPR 60, though markedly slower in the upper reaches, was no slouch either, despite a 25 percent power handicap and pushrod-acutated valves. The engine revved so eagerly that you had to keep a sharp eye on the tach not to go shooting over the 6,000 mark. As it was, I never exceeded 5,800 rpm, nor was the engine held at this figure for more than a brief second or two at a time; yet one got the impression it would have run at 6,000 all day if required to do so. Unfortunately, the SPR60, which was a low-mileage car belonging to Mr. George Williams, a private customer, suffered from clutch slip. This stole a second or two out of every upshift when the engine really wound up and there is no doubt that the acceleration times recorded could be improved upon, although not enough to pose any threat to the superiority of the Climax version. Helping me with a busy pair of stopwatches on the acceleration runs was Goodyear chemist Dave Findlay, an Alfa driver of some repute who really did a bang-up job of timing. There is no sense in trying to compare these two Turners, since they must be judged by entirely different performance standards; but each in its way represents without question top value for your sport-car dollar, whether in performance, design, handling, versatility or general quality. Despite the foul weather, I had a barrel of fun with both cars, both of which embody most of the virtues a dollar-conscious production sports car competition enthusiast could possibly ask for. - John Bentley |